In France, a rumor about the President's wife just earned ordinary citizens criminal convictions and suspended prison sentences, not for threats or violence, but for saying something the state found too insulting to ignore. Today we look at how mockery quietly slid from civil dispute into criminal offense, why prosecutors rather than plaintiffs now decide when speech causes "harm," and how a First Lady's hurt feelings became a matter of public order.

It shows how elastic concepts like cyberbullying give governments a pretext to police expression, how power reshapes the limits of acceptable speech, and why this case should worry journalists, activists, and anyone who speaks online...

|  | It's not every day that a collection of retired European grandees emerges from Brussels' revolving doors to tell everyone how misunderstood the European Union is.

Yet here we are, with Bertrand Badré, Margrethe Vestager, Mariya Gabriel, Nicolas Schmit, and Guillaume Klossa linking arms to pen a sentimental defense of the bloc's new digital commandments.

Their essay, "The Truth About Europe's Regulation of Digital Platforms," aims to assure us that Europe's online rulebook, the Digital Services Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act (DMA), does not constitute censorship. It is "accountability," they say.

In their telling, the DSA is less a blunt legal instrument than a moral document, a kind of digital Magna Carta designed to civilize Silicon Valley's chaotic playground.

"There is no content regulation at the EU level," they wrote, invoking the phrase like a magic spell meant to ward off skeptics.

The laws, they explained, simply make big tech companies "evaluate and mitigate systemic risks" and "act against illegal content." Nothing to see here, just a little transparency, a dash of democracy protection, and the occasional removal of whatever a member state happens to call "illegal."

It is the sort of language that can only come from officials who have spent decades describing regulation as liberation.

The letter was a response to a growing chorus of critics, including former US officials, who say Europe's digital regime gives bureaucrats indirect control over what billions of people can see or say online.

Under the DSA, platforms must scan for "harmful or misleading" content, report their mitigation efforts, and warn users when something gets zapped. Free speech groups have pointed out that when the law tells companies to "evaluate risks to democracy," those companies tend to err on the side of deleting anything remotely controversial.

To them, "mitigation" often means mass deletion.

Badré and company brushed this off. "When we require platforms to be transparent about their algorithms, to assess risks to democracy and mental health, to remove clearly illegal content while notifying those affected, we are not censoring," they wrote.

"We are insisting that companies with unprecedented power over public discourse operate with some measure of public accountability."

When Europe does it, it is not censorship, it is civic hygiene.

To hear them tell it, the DSA and DMA are noble instruments of continental independence.

The authors say the laws protect Europe's "digital, intellectual, and political independence," a phrase that sounds more like a national security slogan than a tech policy.

They cast the legislation as a defense against corporate domination and foreign influence, proof that Brussels has finally grown a spine in the digital age.

But for all the talk of sovereignty and transparency, the system rests on the same principle it claims to restrain: concentrated power over communication.

Only now, instead of tech firms, that power sits inside a supranational bureaucracy that answers to itself.

Within a system where governments define "risk" and corporations enforce it, the line between regulation and speech control becomes a matter of interpretation, and interpretation is the one thing Brussels never runs out of.

In the end, the officials' essay reads like an open letter from an empire that insists it is only protecting you from yourself. | Reclaim The Net exists to defend free speech and push back against the expansion of surveillance.

We report on censorship, government overreach, and the systems being built to monitor, track, and control speech online.

Our reporting, features and guides are read not only by the public, but by people in positions to create change, including lawmakers, legislative staff, nonprofit advocates, attorneys, and policy researchers who rely on accurate, timely information to do their work.

Much of what we publish is freely accessible so it can reach those audiences without barriers. Every article and every email comes with real costs, from research and writing to infrastructure and delivery.

We do not rely on advertisers or corporate sponsors. That independence allows us to report honestly on powerful institutions without pressure or compromise.

While some content is paid, as a gift to our supporters, reader support is what keeps the majority of our work available and ensures it continues to reach the people shaping laws, policies, and legal challenges.

Becoming a supporter is the best way to sustain our work over the long term, but if you prefer, a one-time donation is also a meaningful way to help.

Your support helps keep this reporting alive, relevant, and influential.

A one-time donation of $5, or whatever amount you can afford, directly supports the work that informs decision-makers and strengthens the fight for free speech and freedom from surveillance.

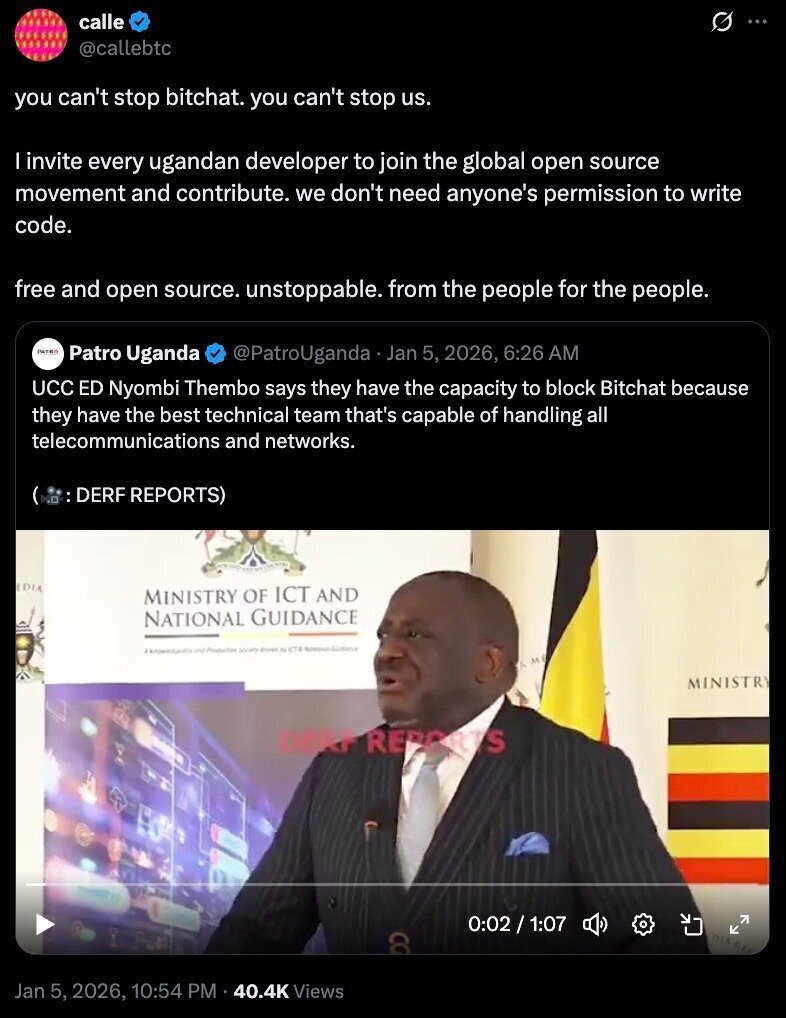

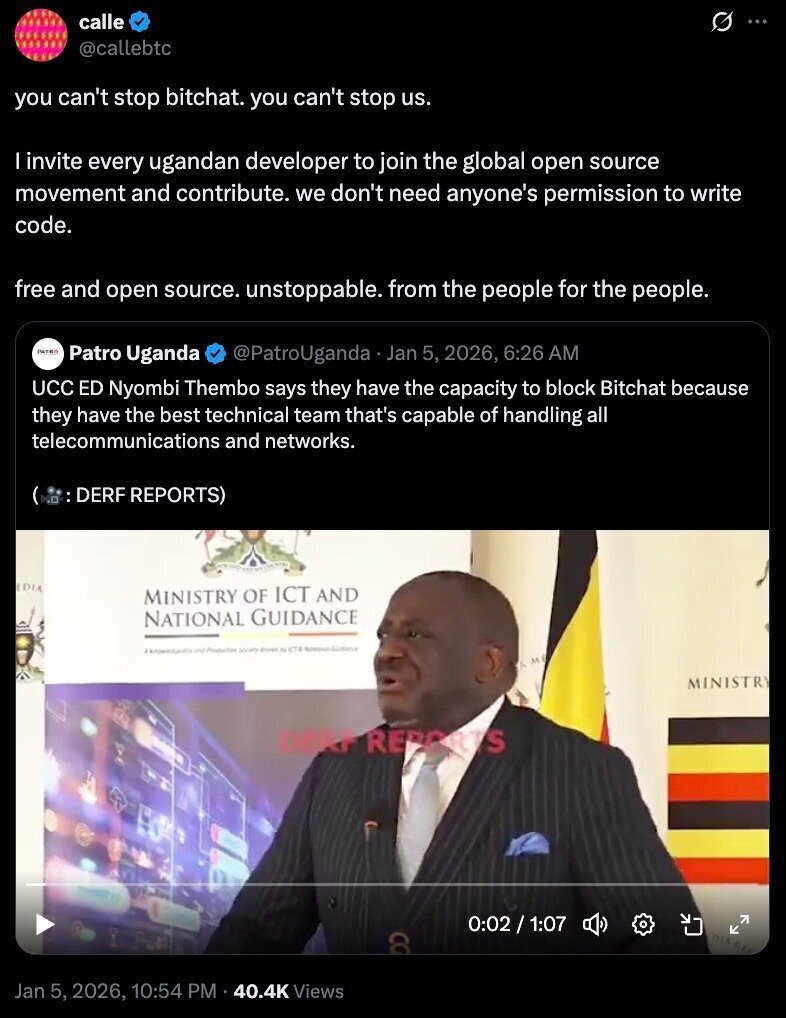

Thank you for supporting independent journalism that makes an impact. | Uganda's government is signaling it may move to block Bitchat, a peer-to-peer messaging platform, just days before voters go to the polls.

The warning came from Nyombi Thembo, the executive director of the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), who said the state's technical units were prepared to disable the service if ordered.

Speaking to reporters, Thembo claimed Uganda had the capacity to take such action, telling NilePost: "We have the highest concentration of software engineers and developers in this country. It is very easy for us to switch off such platforms if the need arises." He also cautioned that Bitchat should not be viewed as a reliable workaround for potential communication limits.

One of Bitchat's open-source developers, known online as "Calle," doubted the government could follow through, saying the platform's design makes blocking it nearly impossible. |  | Bitchat connects users through a Bluetooth mesh network rather than the internet or phone signal. No account setup is needed, and messages move directly between nearby devices.

This architecture allows communication to continue even when authorities restrict online access, as no central servers can be targeted.

The app's user base has expanded rapidly in the past week. Calle reported that installations in Uganda have jumped by several hundred thousand, about one percent of the country's population.

The growth reflects public anxiety over a repeat of earlier information blackouts.

In 2021, the Ugandan government cut internet access nationwide the day before the election, an outage that lasted more than four days.

Social media and mobile payments were also periodically restricted around politically sensitive events.

The unease has deepened after Starlink, Elon Musk's satellite internet service, suspended operations in Uganda following a government request.

Officials said the company lacked a local license, but many citizens saw the move as an early warning of wider controls.

Authorities insist there will be no internet shutdown this time. Thembo called reports of an impending blackout "mere rumors," while the Ministry of ICT's Permanent Secretary, Aminah Zawedde, maintained that the government "has not announced, directed, or implemented any decision to shut down the internet during the election period," describing claims to the contrary as "false and misleading."

Officials said Starlink's suspension was a matter of compliance rather than censorship. Still, the sequence of government interventions has left many skeptical.

President Yoweri Museveni, who has led Uganda for 40 years, is again facing a challenge from opposition figure Robert Kyagulanyi, better known as musician Bobi Wine.

After the 2021 shutdown, Wine alleged that the blackout concealed irregularities in the vote. This election season, he is urging citizens to install Bitchat while they still can, warning in December that the "regime is plotting an internet shutdown in the coming days."

The renewed confrontation over communications technology exposes a deeper struggle over who controls information in Uganda. Bitchat's decentralized model, which relies on direct device-to-device links, makes censorship costly and inefficient, if not impossible. | Getting merchandise for yourself or as a gift helps support the mission to defend free speech and digital privacy.

It also helps raise awareness every time you wear or use it.

Your merch purchase goes directly toward sustaining our work and growing our reach.

It's a simple, effective way to support. Get yours now.

|  | Microsoft's removal of phone activation for Windows and Office is another signal that the company is locking users into a fully connected, account-bound environment where privacy and ownership steadily fade.

In the past, activating Windows could be done privately without linking the computer to any online profile. Users could install the system, call an automated number, and receive a confirmation code. No internet, no account, no tracking.

That layer of independence is gone. Today, activation demands a Microsoft account and an active connection to the company's servers.

Expecting the old process, he found that the phone number now plays a recorded message telling callers that "support for product activation has moved online."

A follow-up text message pointed him to the Microsoft Product Activation Portal, where sign-in is mandatory.

It is easy to miss what has been lost here. Phone activation might have been old-fashioned, but it was more private.

You could install software without revealing your identity or linking it to a broader ecosystem. The new system transforms that private transaction into an interaction within Microsoft's cloud, where every activation, every license, and every key is associated with an online identity.

This is not isolated. In recent versions of Windows, Microsoft has made it increasingly difficult to create local accounts or complete setup without going online.

Now, even activating a legitimate copy of the operating system has become part of the same pattern: tie every function to a Microsoft account, require internet access, and collect the corresponding data.

That approach quietly redefines what ownership means in the digital age.

Buying a license no longer guarantees control over your software; it grants permission to use it under terms that depend on ongoing connectivity.

The computer becomes less of a personal device and more of a terminal inside a managed network. |  | Over the past two weeks, internet users in Pakistan have watched their encrypted connections vanish one after another. Beginning December 22, 2025, major VPNs, including Proton VPN, NordVPN, ExpressVPN, Surfshark, Mullvad, Cloudflare WARP, and Psiphon have been systematically blocked across the country, according to Daily Pakistan.

The blackout follows a government licensing framework that, on paper, regulates VPN providers but in practice gives the state the power to decide which privacy tools are permitted.

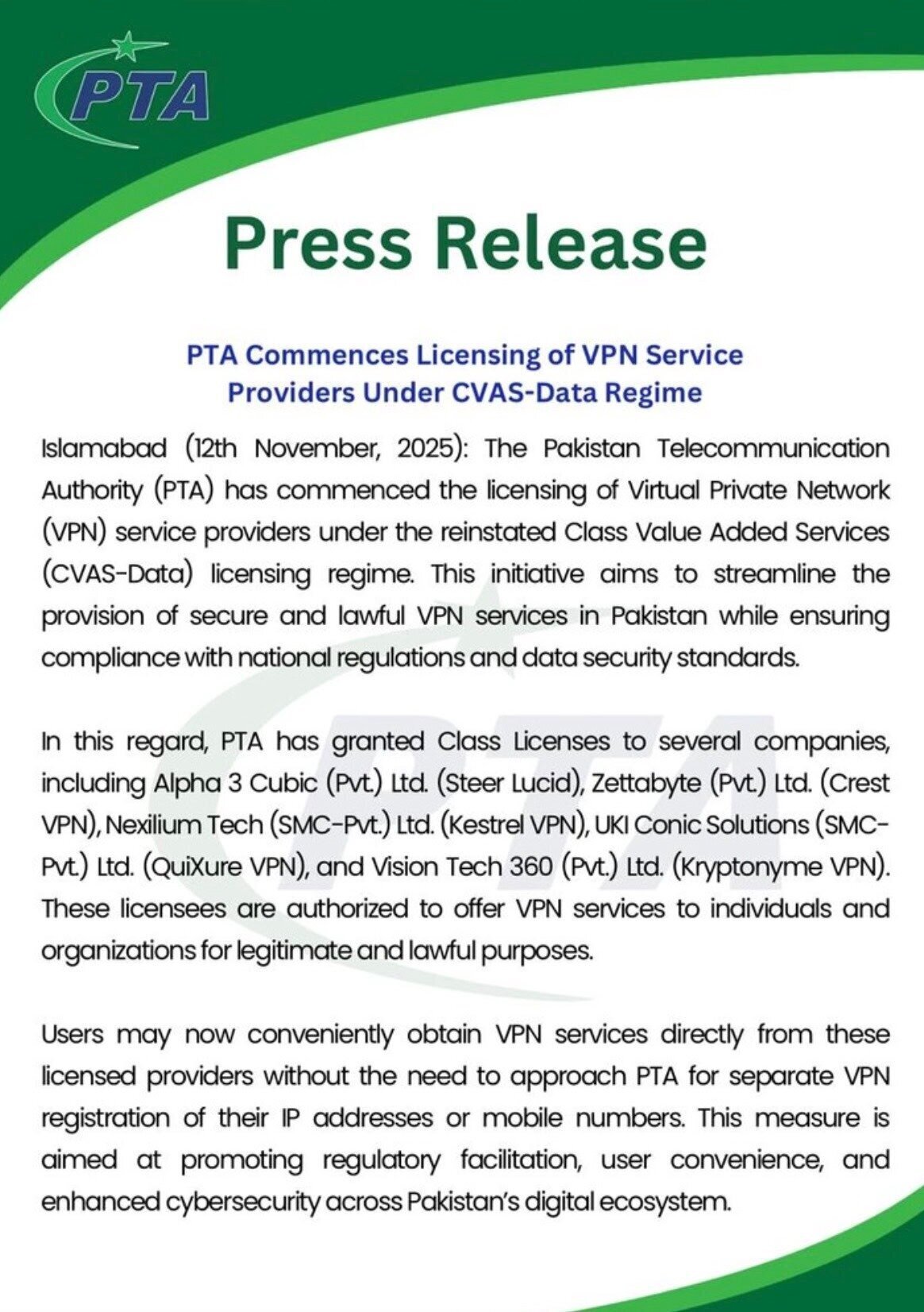

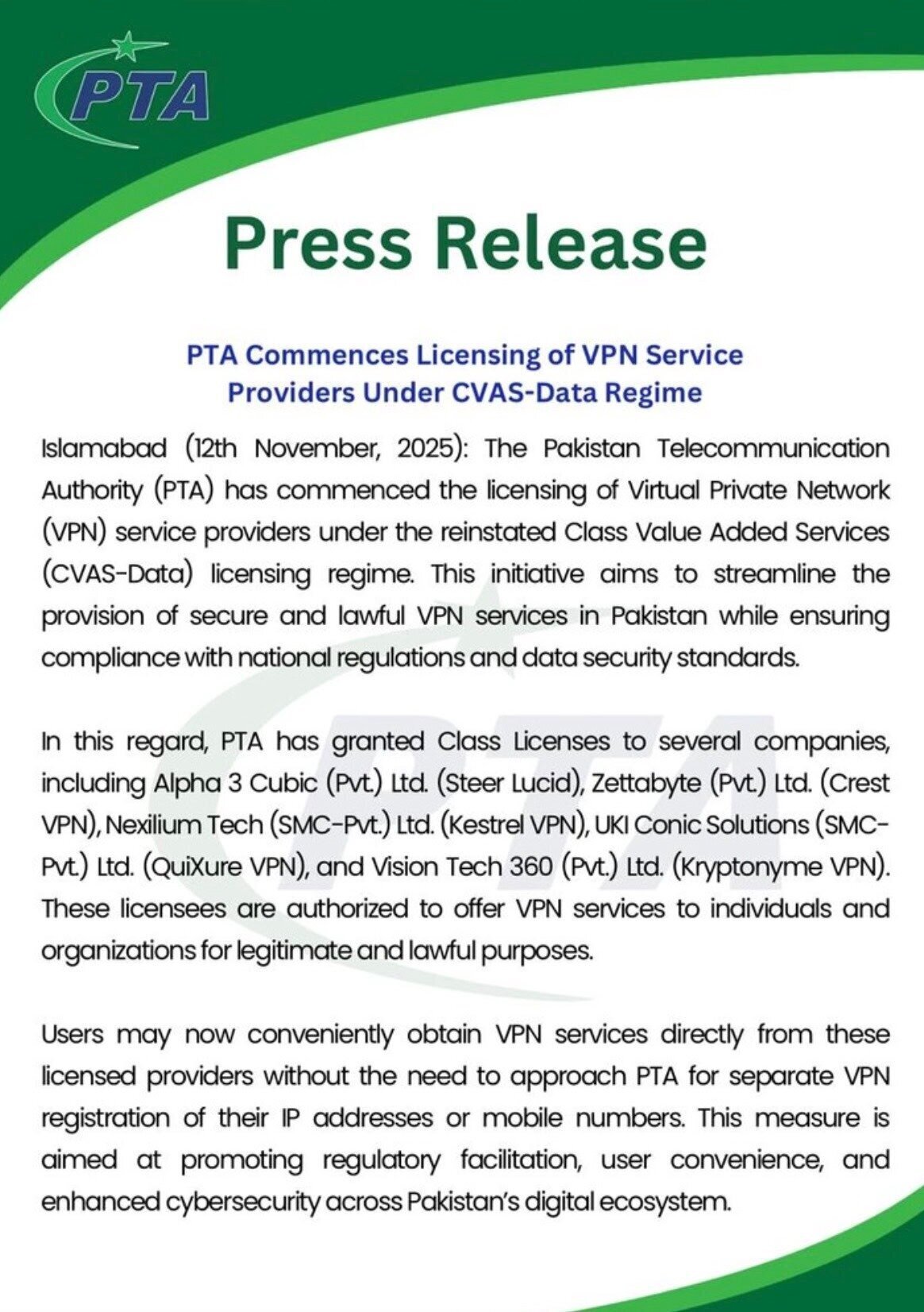

The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) began enforcing its Class Value Added Services (CVAS-Data) licensing rules in November 2025, nearly a year after quietly introducing the policy.

Under these regulations, companies that want to operate legally must install "Legal Interception" compliant hardware and hand it over "to nationally authorized security organizations" at their own expense whenever instructed.

Any VPN not listed as licensed is automatically subject to blocking by domestic internet providers. |  | The bans have not silenced everyone. Some VPNs like Proton have a "Stealth" protocol, Mullvad VPN has a QUIC & WireGuard Obfuscation, and IVPN has V2Ray and Obfsproxy Obfuscation, which can be turned on, helping people bypass some of the VPN blocking attempts.

Officials have promoted the licensing regime as a modernization effort, describing it as a step toward "regulatory facilitation, user convenience, and enhanced cybersecurity across Pakistan's digital ecosystem."

In mid-November, the PTA announced that five domestic firms had already been authorized to provide what it called "secure and lawful" VPN services.

The state's rhetoric masks a deeper problem. Under this model, privacy tools only exist with government permission.

By forcing providers to operate inside the country's legal jurisdiction, regulators gain direct leverage over their infrastructure and data.

This is not a new battle. For years, authorities have tried to outlaw "unregistered" VPNs, only to face legal pushback and technical difficulties.

The licensing system sidesteps those obstacles by creating a closed market that pre-filters which VPNs may function at all.

Pakistan's approach fits a larger pattern of tightening control over online space. Access to platforms like X has been disrupted repeatedly, and digital monitoring capacity has expanded with help from foreign technology suppliers.

A network of licensed VPNs fitted with interception equipment would plug directly into that architecture, ensuring that even encrypted traffic routes through systems capable of inspection.

The opposition Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), founded by former Prime Minister Imran Khan, denounced the government's move, accusing the "dictatorial regime" of censorship.

The party has warned that the new restrictions further isolate Pakistanis from independent information sources at a time of deep political division.

Digital rights groups and business organizations have also raised alarms.

Pakistan's technology sector, particularly its freelance and software export industries, relies on stable and uncensored access to global services.

Previous attempts to curb VPN usage led to slow connections, disrupted client communication, and uncertainty for firms handling foreign contracts. | | Thanks for reading,

Reclaim The Net

| | | |